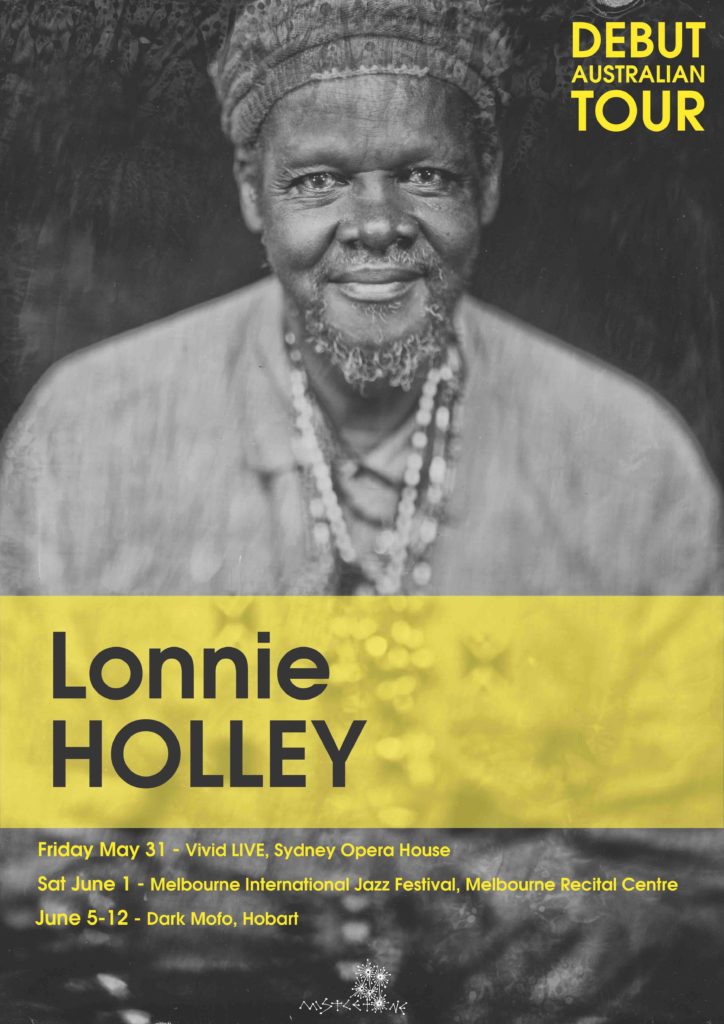

Lonnie Holley

LONNIE HOLLEY TOUR DATES:

- SYDNEY: Friday May 31 at Vivid Live, Sydney Opera House. Tickets on sale Friday March 22, more info here.

- MELBOURNE: Saturday June 1 at Melbourne International Jazz Festival, Melbourne Recital Centre. Tickets & info here.

- HOBART: June 5-12 at Dark Mofo. Two performances, details here.

Mistletone is exhilarated to announce the first ever Australian tour by the great Lonnie Holley and his trio.

Lonnie Holley is an Alabama-born visual artist, musician, and filmmaker. His visual art is in the permanent collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Smithsonian American Art Museum, and many other museums. He has released three critically acclaimed studio albums, including MITH in 2018. His first film, I Snuck Off the Slave Ship, premiered at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival. Like the song that inspired it, the film is a metaphor for African American transcendence.

The expansive American experience Lonnie Holley quilts together is both infinite and finely detailed. Lonnie Holley’s landmark new album MITH (out now on Jagjaguwar via Inertia) is an epic and often arduous journey, one full of struggle, pain and disillusion.

Holley’s self-taught piano improvisations and stream-of-consciousness lyrical approach have only gained purpose and power since he introduced the musical side of his art in 2012 with Just Before Music, followed by 2013’s Keeping a Record of It. But whereas his previous material seemed to dwell in the Eternal-Internal, MITH lives very much in our world — the one of concrete and tears; of dirt and blood; of injustice and hope.

Across these songs, in an impressionistic poetry all his own, Holley touches on Black Lives Matter in “I’m a Suspect”, Standing Rock in “Copying the Rock” and contemporary American politics in “I Woke Up in a Fucked-Up America.” A storyteller of the highest order, he commands a personal and universal mythology in his songs of which few songwriters are capable — names like Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Joanna Newsom and Gil Scott-Heron come to mind.

MITH was recorded over five years in locations such as Porto, Portugal; Cottage Grove, Oregon; New York City and Holley’s adopted hometown of Atlanta, Georgia. These 10 songs feature contributions from fellow cosmic musician Laraaji, jazz duo Nelson Patton, the late visionary producer Richard Swift, saxophonist Sam Gendel and producer/musician Shahzad Ismaily.

MITH‘s grand finale is a moment of levity and hope. It’s a celebration of that purest expression of human joy — dancing. “Sometimes I Wanna Dance” features a jaunty piano riff courtesy of Lonnie’s fellow cosmic traveler Laraaji as Lonnie himself exalts bodily movement in all its forms: from a child’s instinct to move to a groove, to how simply dancing can help us get over our very worst days. In an age of bombastic dance-pop, this minimal groove with nary a drum (!!) is refreshing, buoyant and beaming.

For the accompanying video, Lonnie and a film crew created their own juke joint, Tonky’s Rocket Ship, in the middle of Atlanta and called up some of the city’s blues legends to play the band. The video nods to both the immersive documentaries of Les Blank and the in-the-mix feel of 70s Altman. But more than anything, the message is clear: Free your ass and the mind will follow.

Lonnie Holley’s life story as told by The New York Times:

One night in October, just a couple blocks from Harvard Square, a young crowd gathered at a music space called the Sinclair to catch a performance by Bill Callahan, the meticulous indie-rock lyricist who has been playing to bookish collegiate types since the early ‘90s. Callahan’s opening act, Lonnie Holley, had been playing to similar audiences for two years. A number of details about Holley made this fact surprising: He was decades older than just about everyone in the club and one of the few African-Americans. He says he grew up the seventh of 27 children in Jim Crow-era Alabama, where his schooling stopped around seventh grade. In his own, possibly unreliable telling, he says the woman who informally adopted him as an infant eventually traded him to another family for a pint of whiskey when he was 4. Holley also says he dug graves, picked trash at a drive-in, drank too much gin, was run over by a car and pronounced brain-dead, picked cotton, became a father at 15 (Holley now has 15 children), worked as a short-order cook at Disney World and did time at a notoriously brutal juvenile facility, the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children in Mount Meigs.

Then he celebrated his 29th birthday. And shortly after that, for the first time in his life, Holley began making art: sandstone carvings, initially — Birmingham remained something of a steel town back then, and its foundries regularly discarded the stone linings used for industrial molds. Later, he began work on a wild, metastasizing yard-art environment sprawling over two acres of family property, with sculptures constructed nearly entirely from salvaged junkyard detritus like orphaned shoes, plastic flowers, tattered quilts, tires, animal bones, VCR remotes, wooden ladders, an old tailor’s dummy, a busted Minolta EP 510 copy machine, a pink scooter, oil drums rusted to a leafy autumnal delicateness, metal pipes, broken headstone fragments, a half-melted television set destroyed in a house fire that also took the life of one of Holley’s nieces, a syringe, a white cross.

His work was soon acquired by curators at the Birmingham Museum of Art and the Smithsonian. Bill Arnett, the foremost collector (and promoter) of self-taught African-American artists from the Deep South — the man who brought worldwide attention to Thornton Dial and the quilters of Gee’s Bend, Ala. — cites his first visit to Holley’s home in 1986 as a moment of epiphany. “He was actually the catalyst that started me on a much deeper search,” Arnett says, adding bluntly that “if Lonnie had been living in the East Village 30 years ago and been white, he’d be famous by now.”

Had Holley’s story climaxed right there, with his discovery and celebration — however unfairly limited it has been, if you accept Arnett’s view — you would still be left with an immensely satisfying dramatic arc. But in 2012, at age 62, Holley made his debut as a recording artist. He had been hoarding crude home recordings of himself since the mid-’80s, but never gave much thought to anything approaching a proper release. Then he met Lance Ledbetter, the 37-year-old founder of Dust-to-Digital, a boutique record label based in Atlanta. Ledbetter, who started Dust-to-Digital as a way of bringing rare gospel records — pressed between 1902 and 1960, most them never available before on compact disc — to a broader audience, had never attempted to record a living artist before he heard Holley. “I was hearing Krautrock, R.& B., all of these genres hitting each other and pouring out of this 60-year-old person who had never made a record before,” Ledbetter recalls. “I couldn’t digest it, it was so intense.”

In terms of genre, Holley’s music is largely unclassifiable: haunting vocals accompanied by rudimentary keyboard effects, progressing without any traditional song structure — no choruses, chord changes or consistent melody whatsoever. In many ways, Holley is the perfect embodiment of Dust-to-Digital’s overriding aesthetic: a raw voice plucked from a lost world, evoking the visceral authenticity of a crackling acetate disc. The title of his Dust-to-Digital debut, released in 2012, could double as its own category description: “Just Before Music.” That album and its follow-up, “Keeping a Record of It,” released in September and, for my money, one of the best records of 2013, introduced Holley to a new audience, including members of hip indie-rock bands like Dirty Projectors and Animal Collective, who have all played with him.